|

I first came across

the work of Simon Labalestier some months ago through

a "concatenation of sublunary events" as the

philosopher Pangloss was wont to say. This is the best

metaphor I’ve come across for the process of acquaintanceship

via Internet. Even before our being baptized in the electronic

wash, the very names of the programs we prepare to use

- the browsers - address our persistent desire for communication,

exploration, and discovery. The voyage is often fraught

with difficulties, as it was for the eighteenth-century

Candide and his globe-trotting retinue of metaphysical

companions. We are buffeted about like paper ships on

an unbounded sea, endlessly chasing down a myriad of hyperlinks

through the bottlenecked trade routes of the World Wide

Web, the victims of an infinitude of deliciously dispersive

interests. One can argue the cause and effect of direct

versus vicarious experience via Internet, of the degree

of interactivity necessary for true contact, but as my

ongoing exchange with Simon suggests, the possibilities

are there for those who choose to pursue them.

I mention the Internet

not just as a valuable contemporary "analog"

to material travel, to direct contact, but because it

plays an important role in understanding and interpreting

Simon’s project "Physik Garden: Attracting to

Emptiness," created in collaboration with the artist

Michael Eldridge. The project’s title refers to a

particular seventeenth-century garden cultivated in Europe,

where special herbs and other plants were grown in specific

configurations to heal the minds and bodies of those who

tended it. The artists’ garden leads a triple existence,

being an actual plot of Tuscan land where the two spent

a summer clearing away fifty years of negligence. It also

lives on spiritually, metaphorically, universally in Simon’s

photographs, and has now taken root as a website to be

officially unveiled in January 2000. Like a stem-and-leaf

garden, this website, which first sprouted some months

ago, is both an extension and exegesis of the photographic

prints. In wandering through its seven Gates, one discovers

corners dedicated to a public exchange on themes like

natural healing, contemporary poetry and art, spiritual

experiences, and the historical/archeological secrets

of central Italy.

It's no coincidence

that these were the same concerns occupying the thoughts

of Labalestier and Eldridge as they prepared the "Physik

Garden" photographs: in the formal elegance and haunting

asceticism of the subjects portrayed, these artists are

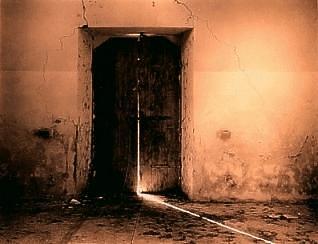

clearly engaged in a spiritual journey. The ramshackle

rooms we see depicted in several of the prints quake with

the feet of the hundreds of those who inhabited them down

through the centuries, generations of the same and then

different families, of grandsons who became grandfathers,

taking their meals at the same and then different tables.

We feel their invisible presence in these rooms, as though

the camera’s shutter had been left open for a millennial

exposure in which the fretful inhabitants and their precarious

furnishings vanish before the insistent permanence of

floor, wall, and ceiling. These are the silent witnesses

to family trees that have come and gone, to a static journey

in time.

With our indoctrination into

the brimming emptiness, we set off with the artists into

the piercing light penetrating the crack in a shuttered

door. In the world that awaits us, the forest, the desert,

we are faced once again with the flowing stillness of

an inner journey, one of deposited time, stretching from

a seventeenth-century Tuscan garden to the earth-girding

Internet.

This article is © Copyright

Willis Davies 2000 and may not be reproduced in part or

in full, in print or electronically without permission. |